Abdominal Wall and Hernias

Abdominal Wall Hernia Types

Abdominal Wall Hernias |

|

|---|---|

Inguinal Hernias

|

|

Anterior Abdominal Wall Hernias

|

|

Pelvic Hernias

|

|

Lumbar Hernias

|

|

Incisional Hernias |

|

Epidemiology

The lifetime risk of developing a spontaneous abdominal hernia is 5% (10% with ultrasound). Among these, inguinal hernias account for 75-80% of cases, while umbilical hernias account for 14% and femoral hernias account for 5%.

Incisional hernia occurs in 10–15 percent of incisions.

The ratio of indirect hernias to direct hernias is 2:1. Inguinal hernias are more commonly found on the right side.

Inguinal hernias are seven times more common in males, while femoral and umbilical hernias are about twice as common in females. Although femoral hernias represent only 10% of inguinal hernias in terms of numbers, they account for 40% of emergencies (incarceration and strangulation). While femoral hernias are seen equally in males and females in terms of numbers, they are four times more common proportionally in females (as other inguinal hernias are less common in females).

The frequency of inguinal hernias increases with age in males (50% at age 75). The incidence of congenital inguinal hernias is inversely proportional to birth weight. Inguinal hernias develop in 32% of infants born weighing less than 1500 g.

Abdominal Wall Anatomy

The abdominal wall can be divided into 3 main regions

- Anterior abdominal wall

- Posterolateral (lumbar) abdominal wall

- Inguinal region

Anterior Abdominal Wall

The upper border of the anterior abdominal wall is the rib margins and the xiphoid process; the lower border is the upper border of the pelvis (coxa); and the posterior border is the vertebral column.

The anterior and lateral abdominal wall muscles are in five pairs. The middle pair of muscles are the rectus abdominis muscles, which run vertically.

The lateral abdominal muscles are in three layers. From superficial to deep (from outside to inside), there are:

- Abdominal external oblique muscles

- Abdominal internal oblique muscles

- Transverse abdominal muscles

Although muscles cover almost the entire abdominal wall, the linea alba and the 4-5 cm space between the rectus muscle and the lateral muscles are muscle-free. Only muscle aponeuroses are found in these regions.

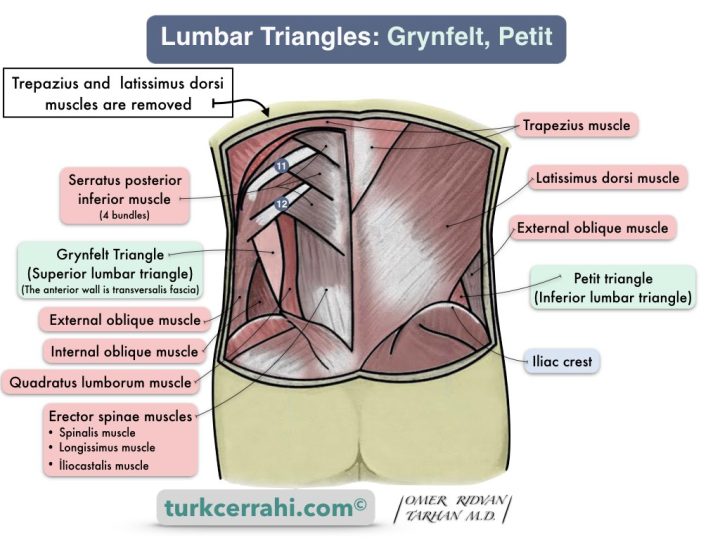

Posterolateral (Lumbar) Abdominal Wall

It consists of three layers. Lumbar hernias also arise from two triangles in this region.

Deep Layer Muscles

- Psoas major muscle (medial)

- Quadratus lumborum muscle (centre)

- Transverse abdominal muscle (lateral)

Middle Layer Muscles

- M. sacrospinalis

- M. obliquus internus

- M. serratus posterior

Superficial Layer Muscles

- External oblique muscle

- Latissimus dorsi muscle

Grynfeltt Triangle Boundaries (Superior Lumbar Triangle)

- Superior: 12th rib, posterior lumbocostal ligament, serratus posterior inferior muscle

- İnferior: Internal oblique muscle

- Posterior: Sacrospinalis muscle

It is larger than the Petit triangle. Most lumbar hernias develop here.

Petit Triangle Boundaries (Inferior Lumbar Triangle)

- Posterior: Latissimus dorsi muscle

- Anterior: External oblique muscle

- İnferior: iliac crest

Inguinal Region

The inguinal region, also known as the groin, is the lower part of the anterior abdominal wall on the right and left sides. The inguinal region is the space between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), which is superolateral, and the lower edge of the thigh, medially. This region is the weakest point of the abdominal wall and includes the imaginary canal called the inguinal canal.

The inguinal region is important because it is where inguinal hernias happen.

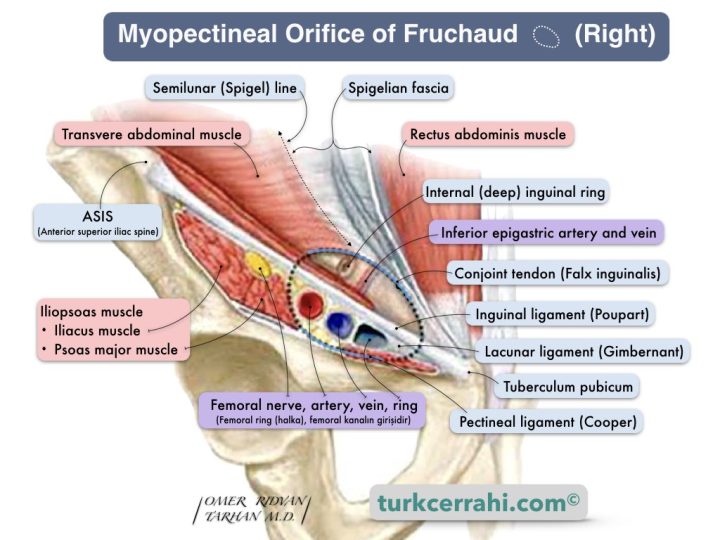

Myopectineal Orifice of Fruchaud

Henri Fruchaud (1894-1961), a French surgeon and anatomist, popularized the term "myopectineal orifice," which is where direct, indirect, and femoral hernias originate.

Boundaries of Fruchaud's Myopectineal Orifice

- Superiorly: Lower borders of internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles (conjoint tendon inguinal previously known as the inguinal aponeurotic falx)

- Medially: Rectus muscle and sheath

- Laterally: Iliopsoas muscle

- Inferiorly: Cooper ligament (pecten ossis pubis)

Development of Inguinal Hernia Surgery

The history of surgical treatment of hernias begins in the 1st century B.C. According to Celsus's writings, Heliodorus was practicing herniorrhaphy. However, standard hernia repairs began to be seen after the 15th century. During this time, the most common surgeries for hernias are castration (removing the hernia along with the testicle), cauterization, and debriding the hernia sac, followed by secondary healing. As might be expected, these treatments often resulted in worse outcomes than the disease itself. Therefore, reliable and knowledgeable doctors seldom refer their patients to surgery.

In 1881, Lucas-Championniere, a French surgeon, performed a high ligation at the inner ring of an indirect inguinal hernia and closed the wound primarily.

In 1884, the Italian surgeon Edoardo Bassini, in addition to the high ligation, reinforced the inguinal canal and posterior wall. He sutured the conjoint tendon to the inguinal ligament. This technique transformed inguinal hernia surgery. For this reason, Bassini is considered the father of modern hernia surgery.

While the Bassini technique was used quite frequently until the last 20-25 years, it has been replaced by tension-free and laparoscopic repairs with synthetic patches, due to high recurrence rates ( up to 30% in the long term)

Following the development of asepsis-antisepsis and anesthesia, the standard treatment in hernia surgery has remained high ligation and reconstruction of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal until today. Although the posterior inguinal wall repair techniques vary, they have become a standard part of hernia surgery.

In order to decrease recurrence, Lotheissen, McVay, Halsted, Shouldice, and others modified Bassini's posterior inguinal wall repair.

In spite of these methods, the recurrence rate remained around 15%, and the tension stitches cause pain. Sometimes, patients had to walk bent over for a long time. Tension was also the leading cause of relapse. With the introduction of synthetic meshes (such as prolene), the tension problem was eliminated, and the recurrence rate was significantly reduced (2%). Therefore, the surgeries employing a mesh were called "tension-free repairs."

Gilbert inverted the hernia sac and occluded the defect with a mesh plug. Rutkow wasn't satisfied, so he added a second flat mesh (as in the Lichtenstein technique) in front of the plug (plug and patch).

Hernias can also be repaired by inserting a mesh into the preperitoneal space. In this technique, a large synthetic mesh, usually prolene, is placed behind the abdominal wall in the inguinal region. The mesh thus covers the myopectineal orifice, which allows for inguinal and femoral hernias. The preperitoneal mesh placement techniques are as follows:

- Kugel (Ugahari) repair technique is very similar to a laparoscopic TEP repair. It is an open technique and the preperitoneal space is accessed using digital dissection.

- Through a lower abdominal incision (midline, Pfannenstiel).

- Stoppa Operation: Bilateral giant prosthetic reinforcement of the visceral sac (GPRVS). The mesh widely covers both myopectineal orifices.

- Wantz Operation: The mesh is placed unilaterally.

- During open surgery (transabdominal), like Wantz or Stoppa

- Laparoscopic surgery

- Trans Abdominal PrePeritoneal (TAPP)

- Total Extra Peritoneal (TEP)

- Intraperitoneal Onlay Mesh (IPOM). The mesh is placed and sutured to the peritoneum without opening the peritoneum.

Incisional Hernias

An incisional hernia is a hernia that develops in the incision. Incisional hernia occurs in 10–15% of abdominal incisions (a high rate). Wound infection increases the incisional hernia rate to 23%.

Causes of Incisional Hernia

- Wound infection

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. steroids)

- Poor surgical technique and suturing, traumatic handling

- Tension in the wound (suture)

- Malnutrition

- Connective tissue diseases

- Advanced age (especially >70 )

- Male gender

- Chronic lung disease and cough

- Constipation

- Benign prostatic hypertrophy (straining)

- Ascites, jaundice, anemia,

- Emergency surgery,

- Type of surgery

Incisional hernias usually occur in the early postoperative period. Incisional hernias are sometimes discovered years later. This is due to the enlargement of small hernias that already existed in the early postoperative period.

The most serious complications of small incisional hernias are incarceration and strangulation.

Repair difficulty and wound infection are the most serious complications associated with large incisional hernias.

The most serious issue with giant incisional hernias is that most of the organs are located outside the abdomen. Following surgery, organ reinsertion may result in abdominal compartment syndrome and sudden death.

Defects in incisional hernias up to 4 cm in diameter may be sutured primarily. According to some surgeons, this limit is 3 cm or even 2 cm. A synthetic mesh should be used for larger incisional hernias (laparoscopic or open technique).

Regardless of hernia size, we believe mesh repair is superior to suture repair in terms of recurrence.