Esophagus - Overview

- Introduction

- Esophagus Tests

- Some Treatments and Definitions Used in Esophageal Diseases

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- Esophagitis

- Barrett’s Esophagus

- Esophageal Ulcer

- Esophageal Stricture (Stenosis, Narrowing)

- Esophageal Motility Disorders

- Corrosive Esophagitis (Esophageal Burn, Caustic Ingestion)

- Mallory-Weiss Syndrome (Tear)

- Esophageal Varices

- Esophageal Webs

- Esophageal Diverticulum

- Esophageal Cancer

1. Introduction

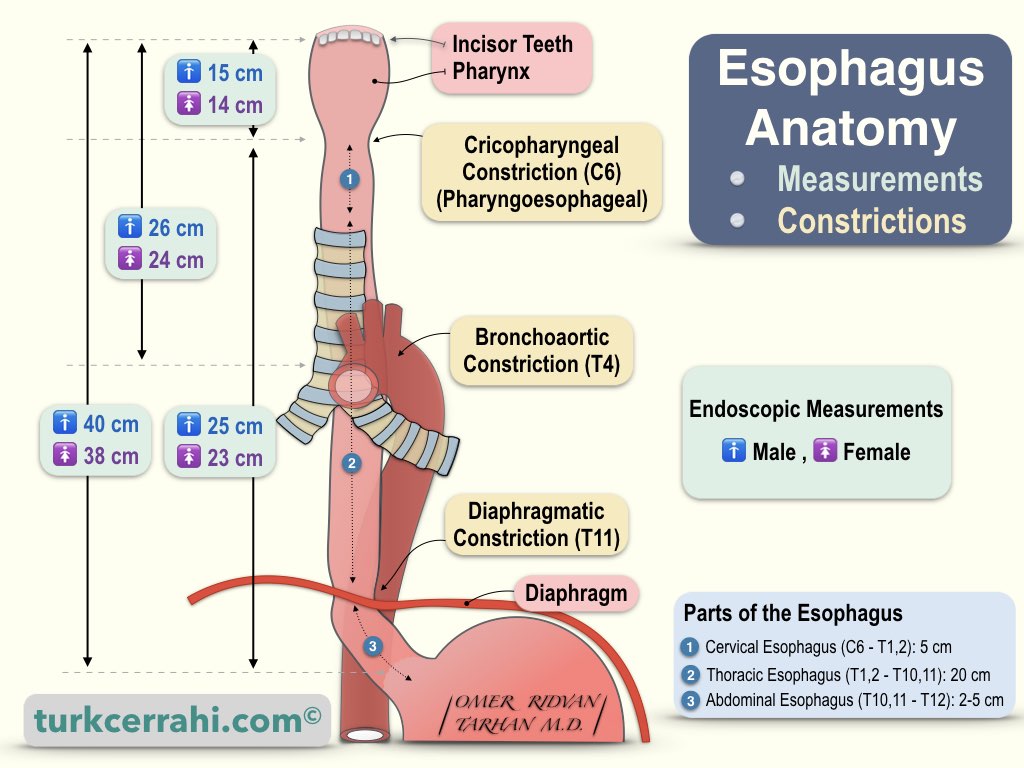

The esophagus is a muscular (smooth muscle) tube that connects the pharynx (pharynx) in the neck and the stomach in the abdomen. Its average length is 25–30 cm. Using an endoscope, the average distance from the incisors to the stomach is 37 cm for women and 40 cm for men. The esophagus is located behind the heart and trachea, in front of the spine.

Gastroesophageal reflux is the most common disease of the esophagus. It makes up about 75% of all esophageal diseases. This article defines the terminology used about the esophagus, common esophageal diseases, tests, and treatments.

2. Esophagus Tests

Upper Gastrointestinal System (GIS) Endoscopy (EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy): A flexible tube with a camera and light is inserted through the mouth (endoscope). The endoscope allows you to examine the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (duodenum).

Esophageal pH Monitoring

A pH-monitoring probe is inserted through the nose into the esophagus for 24 hours. pH monitoring is used to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux and track treatment response.

Barium Esophageal Stomach Duodenum X-ray

The patient drinks barium syrup with the consistency of boza. Barium is an X-ray absorber and appears white on films. Following the passage of barium through the esophagus, an X-ray device (a scope; it can also be recorded as video) is used, and intermittent films are taken. It is most commonly used to diagnose dysphagia etiology, gastroesophageal reflux, and hiatal hernia.

Esophageal Manometry

Manometry means pressure measurement. The esophageal manometry test can be used to diagnose esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, and hypertensive LES (lower esophageal sphincter).

3. Some Treatments and Definitions Used in Esophageal Diseases

H2 blockers

Histamine stimulates acid secretion in the stomach. Some antihistamines, called H2 receptor antagonists, reduce stomach acid and may improve gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and esophagitis.

Proton Pump Inhibitors

These drugs prevent the acid-production pumps in the gastric mucosa from working. This reduces stomach acid, reduces gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) symptoms, and treats ulcers.

Esophagectomy

Surgical removal of the esophagus is generally performed for esophageal cancer.

Esophageal Dilatation

In order to widen a stricture, web, or ring that prevents swallowing, a balloon is passed through the esophagus and inflated, a procedure called esophageal dilatation. Sometimes this procedure is done with special esophageal plugs (expanders) called Maloney dilators.

Band Ligation for Esophageal Varices

By attaching additional pieces to the endoscopy device, esophageal varices are banded (tied) with small bands like rubber buckles. Banding results in necrosis and shedding of the varicose vein. The bleeding from the varicose veins is stopped, and the area around the band heals with fibrosis (scarring).

Endoscopic Biopsy

Endoscopic biopsy: Small pieces of tissue are removed with instruments during endoscopy. The instruments advanced through the working channel of the endoscope. The removed tissue pieces are sent to the pathology department for microscopic examination.

4. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Gastroesophageal reflux disease occurs when stomach contents (acid) frequently reflux into the esophagus. Gastric acid irritates the esophagus (esophagitis) and causes heartburn, retrosternal burning, coughing, or hoarseness.

Many people experience acid reflux sometimes. Reflux becomes a disease when there is mild acid reflux at least twice a week or moderate to severe acid reflux once a week.

Most people can overcome gastroesophageal reflux disease with lifestyle changes and medications. However, some patients may need surgery to relieve their symptoms.

5. Esophagitis

Esophagitis is inflammation of the esophagus. Among the following causes, gastroesophageal reflux (stomach acid) is the most common. Esophagitis can cause painful and difficult swallowing (dysphagia) and chest pain.

- Reflux esophagitis

- Eosinophilic esophagitis (usually of allergic origin)

- Lymphocytic esophagitis

- Drug-induced esophagitis (Swallowing a pill with little or no water)

- Painkillers such as aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen sodium

- Antibiotics such as tetracycline and doxycycline

- Potassium chloride used to treat potassium deficiency

- Bisphosphonates (e.g. Alendronate, Fosamax) used to treat osteoporosis

- Quinidine is used to treat heart problems.

- Infectious esophagitis is rare but common in people with weakened immune systems, such as people with HIV/AIDS or cancer, diabetes, cancer, use of steroids or antibiotics

- Bacterial infection

- Viral infection

- Fungal infection

6. Barrett’s Esophagus

Barrett's esophagus develops when the esophageal mucosa, which is constantly exposed to acid, transforms into the small intestine mucosa (intestinal metaplasia). Barrett's esophagus often develops in people with long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Barrett's esophagus increases the risk of developing esophageal cancer. Despite the low risk, routine endoscopy checks for dysplastic (precancerous) cells are essential. If precancerous cells are discovered, they can be treated to prevent esophageal cancer.

7. Esophageal Ulcer

An esophageal ulcer is a type of peptic ulcer. A peptic ulcer is an ulcer caused by acid. An esophageal ulcer is painful. In reflux, both acid and Helicobacter pylori infection cause esophageal ulcers. Rarely, fungal and viral infections can also cause esophageal ulcers.

8. Esophageal Stricture (Stenosis, Narrowing)

An esophageal stricture occurs in three types of diseases. Peptic strictures account for 70–80% of all cases of esophageal strictures.

- Intrinsic Diseases (Esophageal Wall)

- Inflammation (esophagitis, peptic strictures)

- Fibrosis or neoplasia (cancer)

- Congenital (esophageal atresia)

- Caustic esophagus

- Iatrogenic (anastomotic stricture, sclerotherapy, radiotherapy.

- Extrinsic Diseases (External Compression, etc.)

- Invasion of another cancer (thyroid, stomach, lung cancer)

- Compression of the lymph nodes.

- Diseases Impairing the Function of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES)

- Achalasia

- Nutcracker esophagus.

9. Esophageal Motility Disorders

Achalasia

Achalasia is caused by the progressive degeneration of myenteric ganglion cells. The myenteric plexus is a nerve network located between the longitudinal (outer) and circular (inner) muscle layers of the esophagus. In a pathologic examination, a decrease in ganglion cells is detected. Ganglion degeneration impairs peristalsis in the distal esophagus, and the lower esophageal sphincter cannot relax. Achalasia is a rare disease that affects one in 10,000 people. Between the ages of 25 and 60, the ratio of men to women is equal.

Symptoms of Achalasia

The most common symptoms in achalasia patients are dysphagia for solids (91%) and liquids (85%), as well as regurgitation of soft, undigested food or saliva (76-91%). Achalasia starts insidiously and progresses slowly. Patients often live with these symptoms for years (an average of 4.7 years) before being diagnosed. These patients are misdiagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), psychosomatic disease, and other conditions.

Diagnosis of Achalasia

- On direct radiographs, mediastinal enlargement and absence of gas in the gastric fundus

- Barium Esophagogram (barium swallow)

- Enlargement of the esophagus (megaesophagus; >6 cm)

- Elongation and angulations in the esophagus, sigmoid appearance,

- Bird's-beak appearance at the esophagogastric junction

- Loss of peristalsis (aperistalsis), and delayed passage of barium into the stomach.

- Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- Food debris in the esophagus

- Enlarged esophagus

- The lower esophageal sphincter does not open spontaneously with air.

- Esophageal Manometry

- Loss of peristalsis in the distal ⅔ part

- Inability to relax in the lower esophageal sphincter

- High-resting pressure

Treatment of Achalasia

The goal of treatment is to decrease the lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

- Medication

- Nitrates

- Calcium channel blockers)

- Endoscopic Interventions

- Endoscopic pneumatic dilatation (with balloon)

- Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM), full efficacy has not yet been proven

- Botulinum toxin injection (botox)

- Surgical esophago-cardio-myotomy (open / laparoscopic) + fundoplication.

Diffuse (Distal) Esophageal Spasm (DES)

Diffuse esophageal spasm is characterized by uncoordinated and non-propulsive distal esophageal contractions. Normally, coordinated and sequential esophageal contractions advance food, similar to a screw pump. DES is defined by traditional manometry as 20% or more simultaneous contractions with an amplitude greater than 30 mmHg. Although the majority of DES patients have normal LES relaxation, about one-third have elevated resting pressure or incomplete relaxation. This disease causes dysphagia and chest pain.

Nutcracker Esophagus (Hypertensive Peristalsis, Spastic Nutcracker, Hypercontractile (jackhammer) Esophagus)

In the nutcracker esophagus, there are normal sequential (coordinated) contractions, but the amplitude and duration of the contractions are long. The nutcracker esophagus is defined in conventional manometry by high-amplitude peristaltic contractions in the distal esophagus that exceed 220 mmHg after swallowing the liquid. Many nutcracker esophagus patients also have hypertensive LES. Unlike diffuse esophageal spasm, it is usually asymptomatic.

The nutcracker esophagus is also called hypertensive peristalsis, spastic nutcracker, hypercontractile esophagus, and jackhammer esophagus.

Hypertensive Lower Esophageal Sphincter

In conventional manometry, the hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter has a resting LES pressure of more than 45 mmHg in the mid-respiratory phase. Unlike diffuse esophageal spasm, it is usually asymptomatic.

10. Corrosive Esophagitis (Esophageal Burn, Caustic Ingestion)

Caustic or corrosive substances are usually strong acids or bases. Children accidentally drink lye and stop when they taste it, so they only drink a small amount. Young people and adults usually drink more lye because they drink caustic with suicidal intent.

Acids are drunk in smaller amounts than bases because they immediately burn and hurt the mouth and pharynx when consumed.

Consuming caustic materials may cause esophageal and stomach perforations during the acute phase. In the chronic phase, esophageal stenosis may develop, causing swallowing difficulties.

The damage caused by caustic materials depends on:

- The amount of caustic material

- Properties and concentration

- Duration of tissue contact

The damage mechanisms of acids and bases are different. Bases dissolve tissue and lead to easier perforation. Acids cause damage called coagulation necrosis, which limits the penetration of acid into the tissue, and perforation is more difficult.

When drinking a base (e.g., bleach), vinegar, lemon juice, or orange juice neutralizes the base and is beneficial. When acid is drunk, giving milk, egg whites, or an antacid syrup tablet to the patient neutralizes the acid and is beneficial. The patient should not induce vomiting because the esophagus will be exposed to the same chemical again. Surgery is required if an esophageal or stomach perforation occurs. In the chronic phase, strictures are treated with dilatation or surgery.

11. Mallory-Weiss Syndrome (Tear)

Mallory-Weiss syndrome develops due to severe vomiting. It is a mucosal laceration (tear, intramural dissection) that runs along the distal esophagus and proximal stomach. Tears often (70%) also cause hemorrhage (hematemesis from the submucosal arteries).

Mallory-Weiss syndrome is the cause of 1–15% of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Heavy alcohol consumption is frequently the cause of severe vomiting. Studies have shown that individuals with hiatal hernias are more prone to rupture. Mallory-Weiss tears can be caused by vomiting during pregnancy or liver cirrhosis, straining, heavy lifting, severe coughing attacks, nasogastric tube insertion, and gastroscopy.

Symptoms

Mallory-Weiss syndrome is characterized by hematemesis (bright red blood or coffee-ground emesis). Chest and epigastric pain may accompany bleeding.

Diagnosis

Endoscopy reveals a longitudinal mucosal tear extending from the distal esophagus to the cardia. A single (70%) or multiple mucosal tears (30%) may occur. A hiatal hernia may also be present. These tears heal within 24 to 48 hours. Therefore, they may not be seen if the endoscopy is delayed.

Treatment

If the bleeding is severe, the patient should be hospitalized for hemodynamic stabilization. If there is active bleeding on endoscopy, sclerotherapy is applied. An intravenous proton pump inhibitor is used as a medical treatment in cases of severe bleeding, and an oral proton pump inhibitor is used as an outpatient treatment in cases of mild or stopped bleeding. If necessary, antiemetics are added to the treatment.

12. Esophageal Varices

Varicose veins are enlarged, elongated, and thin. Cirrhosis-related esophageal varices typically appear in the lower esophagus. Normally, gastrointestinal venous blood flows into the liver. After passing through the liver, blood is poured into the inferior vena cava. In chronic liver disease (cirrhosis), fibrosis (scarring) develops in the liver tissue. Liver fibrosis impairs blood flow within the capillary network (sinusoid; liver tissue capillary system). As a result, venous pressure rises throughout the gastrointestinal tract, causing portal hypertension. Portal hypertension causes varicose vein dilation in the gastrointestinal system. Varices in the esophagus and stomach are significant because they can bleed.

Symptoms

The most common cause of esophageal varices is portal hypertension due to liver cirrhosis. Unless they bleed, esophageal varices may not cause any symptoms. Hematemesis (bloody vomiting), melena (bloody stools), and shock (first weakness, then loss of consciousness, and a potentially fatal coma) are all symptoms of esophageal-variceal bleeding. Cirrhosis-related esophageal varices may also exhibit the following signs and symptoms: jaundice, bleeding diathesis (easy injury and bleeding), malnutrition, weakness, abdominal ascites (causing abdominal swelling), confusion, and coma.

Diagnosis

Esophageal varices can be detected in endoscopy controls performed in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ultrasonography and computed tomography both show splenic and portal vein enlargement.

Treatment

The treatment of esophageal varices can be summarized as preventing and stopping bleeding.

- Prevention of Variceal Bleeding (Prophylaxis)

- Varicose veins, which are thought to bleed during the endoscopy controls, are ligated endoscopically (endoscopic band ligation).

- Use of beta-blockers to reduce portal pressure.

- Stop Variceal Bleeding

- Endoscopic Hemostasis: Both diagnosis and band ligation are performed at the same time.

- Medical Therapy: Octreotide (Sandostatin) reduces portal vein flow and pressure

- TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt): The liver vein (hepatic vein) is entered via the internal jugular vein in the neck. Then, the portal vein is entered passing through the liver tissue. A thin catheter is placed between these two veins (hepatic vein - pırtal vein). This procedure is performed by an interventional radiologist and reduces portal vein pressure by diverting blood flow from the portal vein to the hepatic vein.

- Liver transplantation

13. Esophageal Webs

Esophageal webs are thin, ring-shaped membrane-like structures that partially block the esophageal lumen. They are less than 2 mm thick. Esophageal webs are usually asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients typically present with occasional dysphagia for solids (difficulty swallowing). It usually originates from the anterior side of the cervical esophagus.

Esophageal Ring (Schatzki Ring)

The esophageal ring is the concentric (symmetrical), 2–5 mm-thick tissue that narrows the esophageal lumen. Schatzki rings are thicker and more symmetrical than the esophageal webs. They are usually found in the distal esophagus. Schatzki rings are usually mucosal. They can, however, become muscular as a result of lower esophageal sphincter hypertrophy.

The most common esophageal ring is the Schatzki ring, at the squamocolumnar junction (Z line). According to some studies, hiatal hernia is found in 97% of people who have Schatzki rings.

Plummer-Vinson Syndrome (Paterson-Brown-Kelly Syndrome, Sideropenic Dysphagia)

Plummer-Vinson syndrome also known as Paterson Brown-Kelly syndrome is defined by classic triad of iron deficiency anemia, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), and the cervical esophageal web. The following components can also be found in this syndrome: glossitis, angular (commissural) cheilitis (wound around the mouth), koilonychia (pit nail), splenomegaly, and goiter. Since Plummer-Vinson Syndrome is a risk factor for esophageal and pharyngeal squamous cell cancer, its recognition and treatment are important. After iron supplementation, dysphagia usually resolves before the anemia improves. If the stenosis is severe, an endoscopic balloon or dilator is used to dilate the esophagus.

14. Esophageal Diverticulum

Zenker's Diverticulum (Pharyngoesophageal Diverticulum)

Zenker's diverticulum is both a pulsion diverticulum and a pseudo-diverticulum. Zenker's diverticulum is formed by the protrusion of the mucosa and submucosa; it lacks a muscle layer. The Zenker diverticulum develops from the Killian's triangle (or Killian dehiscence), which is located between the cricopharyngeal and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles. Symptomatic Zenker diverticulum is five times more common in men. It is seen in middle age, between the ages of 70 and 80.

Traction Diverticulum of the Esophagus

A traction diverticulum is a true diverticulum in the middle of the esophagus that includes all esophageal layers (mucosa, submucosa, and muscle layers). The esophageal wall undergoes full-thickness recession due to tuberculosis-induced mediastinal lymphadenitis or other causes. It is usually asymptomatic and requires no treatment.

Epiphrenic Diverticulum

The epiphrenic diverticulum is located on the right, just above the lower esophageal sphincter. It is both pulsion (pressure) and pseudo-diverticulum (it is not full thickness; there is no muscle layer). Frequently, epiphrenic diverticulum is accompanied by achalasia. Therefore, Heller myotomy (esophago-cardiomyotomy) should be added to diverticulectomy.

15. Esophageal Cancer

The vast majority of esophageal cancers (95%) are squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas. Esophageal cancers originate primarily in the esophagogastric junction and cardia. The incidence of esophageal cancer is 16 times higher in North and East Africa and East Asia than in Central America.

A vegetable-poor diet, hot foods, smoked foods, smoking, alcohol, and Barrett's esophagus are risk factors.

Esophageal cancer manifests itself with progressive difficulty swallowing and weight loss. Sometimes occult bleeding causes iron-deficiency anemia. In early-stage esophageal cancer (T1-2, N0, M0), chemotherapy and radiotherapy follow esophagectomy, whereas in T3-4 cancers, surgery follows chemoradiotherapy. Resection is not recommended in metastatic esophageal cancer. The peritoneum, lung, bone, adrenal gland, brain, and liver are the most common sites for esophageal cancer metastasis.